A recent Vulture piece considered the appeal of Substack. “Part promotional platform, part social-media site, part venue for rambling journal entries, Substack is attracting an increasing number of people who write literature for a living,” wrote Emma Alpern, before going on to praise the site’s hyper-specific offerings.

In our zip code, novelists like Ottessa Moshfegh, George Saunders, and Junot Díaz are all making hay on the site. Meanwhile journalists, lately ousted from their mastheads in legacy media, are starting to slouch towards Substehem. Commentators like Margaret Sullivan, Jennifer Rubin, and former MSNBC host Mehdi Hassan can all be found fresh in the stacks.

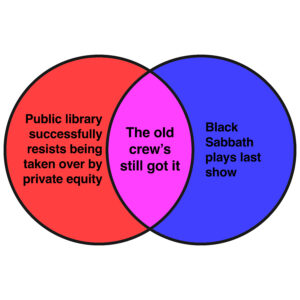

But over the past few years, Substack’s lost some shine. In 2022, the site was knocked for platforming TERF-y hate speech. At the time, Hamish McKenzie, a principal founder, jumped to defend the site’s “decentralized approach” to content moderation. Many writers, like Grace Lavery, abandoned sub shortly after.

Last year, the company was embroiled in scandal again after an Atlantic investigation revealed “scores of white-supremacist, neo-Confederate, and explicitly Nazi newsletters” on the platform. An open letter from 247 Substackers Against Nazis went unanswered. There were more defections, more hand-wringing calculations. But the site has continued to attract writers, readers, and mostly warm coverage, as we see above.

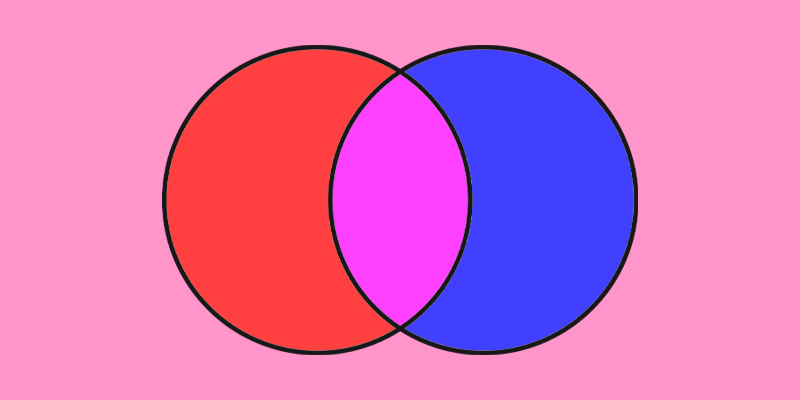

Given that we now have several well-publicized examples of management’s shaky ethics, the case against the platform feels fairly clear. Being a private equity venture, Substack directly profits from its creators, hateful and hopeful alike. So if you make or send money off subscriptions, the big bad board bites off some of that revenue.

And though Substack’s leaders could intervene on the moderation front, or even equivocate with a mealy-mouthed pledge to look into their Nazi problem, they’ve consistently favored a bottom line. Mostly, leadership has stuck to the ole free speech playbook we last saw deployed on Elon Musk’s X.

On the other hand, you could argue that every digital platform backed by venture capital is ethically compromised. And for writers who’ve sunk a lot into building flocks and relationships on the site, it’s hard to argue that another shop would be a whole lot better for the world. This makes fine sense, especially if you’re bound to make a living off it. But that brings us to the bubble problem.

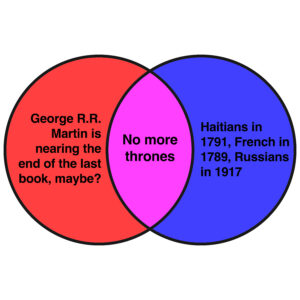

In a June 23rd newsletter, Ana Marie Cox, author and founder of the political blog Wonkette, predicted a Sub-comeuppance. Cox is one of a growing group of business soothsayers who believe that as Substack grows, the harder it will become for newcomers—and so, the money men—to make their money.

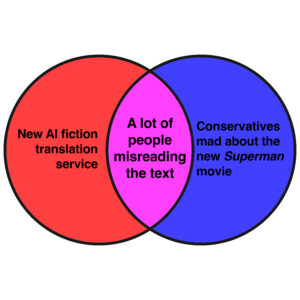

As we’ve seen occur with the big TV streamers, any individualizing platform risks subscription fatigue. Writing in Wired, Steven Levy noted that amassing stacks in lieu of “full-fledged publications” is “a terrible value proposition.”

Likewise, Cox predicts that as the site’s pressure to grow increases, “so will the incentives to double down on the kind of polarizing, high-engagement content that gets attention even if it poisons the well.” This could leave creators who’ve gambled to stay on the stack out to dry, both ethically and financially.

And at what cost, really? My colleague Drew Broussard hates the whole phenomenon of attention-trap platforms. “It’s extractive SV capitalism at its worst,” he told me. “The world doesn’t require your newsletter.”

*

Personally, I get being stuck on this one. In a constantly contracting media ecosystem, it’s hard to blame writers who’ve built followings anywhere. I read and admire several stacks, including these. And when it comes to the exodus question, I tend to flock with other writers who have fled the platform for the No Malice Palace. Writers who go out of their way in goodbye notes to say they don’t judge anyone else for sticking around.

On the attention-trap phenom in general, I’m a little less charmed by newsletters than some because 1) I tend to love editors, and 2) especially if you want me to pony up, I’d prefer an idea that’s fully baked. If everyone’s blogging for free, I figure we might as well Tumbl back to where we came from, in the glorious mid-aughts. But I know this skirts the practical aspects of today’s gig and hustle economy.

That said, if you’re a newsletter creator starting out or contemplating a big change, you should know there are alternatives to Substack. Like Beehiiv, which markets itself as more of a distribution tool than a social media platform. By making itself structurally distinct from the baddies, management hopes to sidestep the whole content moderation snafu.

There’s also Ghost, the non-profit, open access site that Platformer jumped to in 2024. And Ana Marie Cox uses Buttondown. My pal, the writer Gemma Kaneko, also likes that one for its “nuts and bolts interface” and minimal tracking. She says it feels like a zine, in the best way.

But Drew’s point about the why of it all—especially when it comes to making money—does stick to my skin. “A different newsletter platform isn’t all I want, because newsletters aren’t the answer to a disintegrating media ecosphere,” wrote Cox, in a similar spirit. “We need a world where a social safety net protects risky writing. The idea that we can hustle our way to safety will only push us closer to collapse. We don’t need better tools as much as we need each other.”